Have you felt stretched too thin lately? Worn out or burnt out? You are not alone. Our culture fights against limits and pushes against the boundaries that frame our lives. We don’t want to miss out. “More is better”, we believe, so we try harder to experience more to get more. Yet, there is always more. This leaves us unsatisfied, angry and exhausted.

Our marketing memes show our belief that “more is better.” Just add the word “unlimited,” and customers will buy whatever you sell. Because we believe the good life is found beyond our boundaries, we always strive for more. We war against the boundaries of our lives but end up fatigued, frustrated, fearful, and flat—in a word, lifeless. How is it that “more” leaves me feeling “empty”?

In a world where limitless is life, we fantasise about superheroes. Yet we are creatures, not gods. We are limited beings, blessed to thrive within our boundaries. Pete Scazzero lists some limits that we all can relate to. My life on this earth is a blessing, but it is brief; I can’t escape death. My mind has its limits, regardless of my learning. My personality or temperament has its strengths and weaknesses in every situation. My gifts are great, but it has their limits. My family or origin gifts me within a particular cultural, financial and social context; this is a blessing, but it holds its limits. Whether I am rich or poor, black or white, male or female – each attribute empowers and impedes me in life. Likewise, my own past (actions and experiences) holds great treasures, but with its limiting consequences. Each season of life has its gifts and limitations; we can’t change that – only embrace the season with its invitation and limitation.

The Apostle Paul also wrestled with his human limitations. In 2 Corinthians 12:7-10, he recounts a life-altering meeting with Jesus that changed his perspective on limits. “…I have received such wonderful revelations from God. So, to keep me from becoming proud, I was given a thorn in my flesh, a messenger from Satan to torment me and keep me from becoming proud. 8 Three different times I begged the Lord to take it away. 9 Each time he said, “My grace is all you need. My power works best in weakness.” So now I am glad to boast about my weaknesses so that the power of Christ can work through me. 10 That’s why I take pleasure in my weaknesses, and in the insults, hardships, persecutions, and troubles that I suffer for Christ. For when I am weak, then I am strong.”

Paul’s reference to “a thorn in the flesh” is often misunderstood as a slight pinch in the foot. But, Pete Scazzero explains that the original language referred to a pike-like military defensive barrier (see image below). Today, Paul might have used “a sharp palisade fences or barb-wire in my flesh.” Pressing against this barrier caused him anguishing pain and left him feeling frustrated (angry and powerless).

Many have speculated about this “thorn in the flesh” in Paul’s letter. Some read Paul’s “thorn in the flesh” as a painful or shameful bodily obstacle that inhibited his life or mission. It might have been a speech impediment, like Peter’s lisp (Matthew 26:72-73) or Moses’ stuttor (Exodus 4:10). Others think Paul lived with a painful and debilitating eye infection (see Galatians 4:13-15, 6:11). Some sceptics believed Paul suffered from episodes of epilepsy (because of his disabling visions, as in Acts 9:3-9 and 2 Corinthians 12:7. Yet, others argue that Paul used the phrase “thorn in flesh” metaphorically to refer to emotional pain caused by his loneliness or the ongoing opposition by the Judaizers who constantly discredited his message and character. A last group believed that Paul’s torment was only spiritual, caused by some demonic “messenger from Satan”.

Whatever it was, we know that this “thorn in the flesh” was painful and limiting. Paul suffered from it and could not fix the problem himself. His prayers were not answered either – the Lord did not relieve him of this burden either.

Our culture does not readily accept the limits of “no.” Our culture believes you can do anything and everything if you put your mind to it. Not accepting limits or “no” leaves us exhausted, angry, and inhibited. What can we learn from Paul’s message?

Flourishing within limits

The Bible includes examples of people who served God with tremendous freedom despite their limitations. These limits did not hamper the ministry or legacy of these faith heroes; instead, these faith heroes flourished within these limits, often because of these limits. Jesus taught that “blessed are the meek, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” Meekness means submission to restraints as a horse submits to the saddle and bridle of a rider. We are blessed (better off) when we learn to rest within our constraints and trust that God can and will give us goodness here where we find ourselves.

Moses’ life-long speech impediment did not prevent him from fulfilling his call. It seems ironic that, despite all the miracles performed through Moses, the Almighty did not heal him of his stutter. God chose to appoint a man with a speech impediment as his spokesman. In his weakness, God’s power was made known.

David was small, the youngest and most neglected member of his family. Yet God chose this insignificant shepherd boy to deliver his people from the Philistine giant and unite them in one glorious kingdom.

Daniel and his friends were enslaved, yet his God’s sovereignty was made known through these young Hebrews as they faithfully served their captors in the palace.

John the Apostle was a political prisoner on the Island of Patmos, far removed from the oppressed churches under his care. Yet here, God revealed powerful visions with messages of hope that have served the church for millennia.

Likewise, Paul’s most potent and lasting ministry was from within a Roman prison, as he learned to rely on God’s grace. He discovered that these impediments taught him not to become proud (happy, independent, or self-reliant) but rather to rely on God’s grace. “My grace is all you need. My power works best in weakness.”

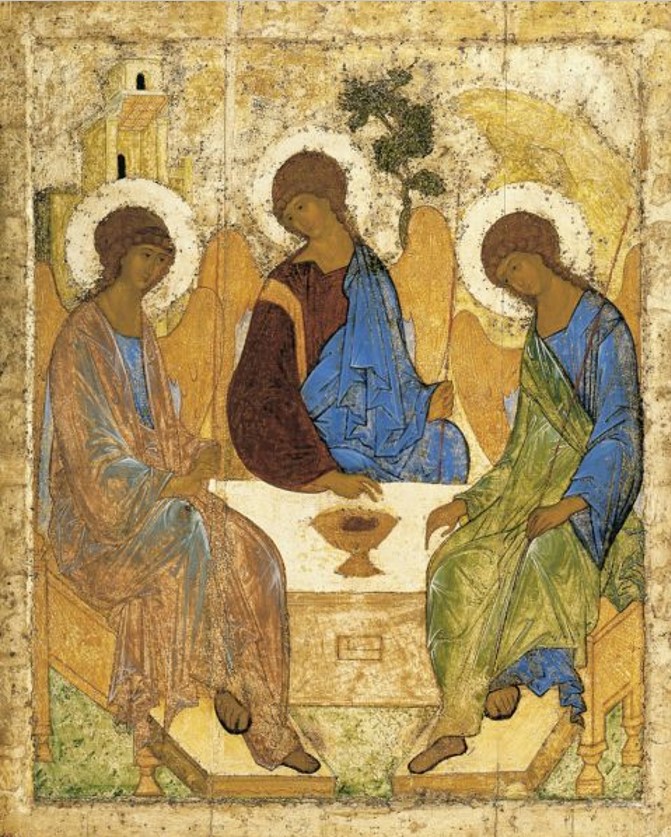

Jesus Christ is God in the flesh, living as a poor Jewish boy raised in an insignificant rural village while the mighty Roman Empire ruled his people. This God suffered hunger, ridicule, shame, betrayal, torture and violent death. Through this, God restored his kingdom and delivered all who trusted in him from death.

My limitations as gifts

Paul discovered that the “thorn in his flesh” did not diminish his life; his life and legacy expanded as he embraced his limitations.

- Paul’s limitation taught him humility – a life that relies on God’s grace, not his own strength and wisdom.

- Resting in his limitation gives him a revelation of God’s nearness and grace.

- His limits were the means to intimacy, the reason to draw near to God and trust him more.

- Paul’s limiting imprisonment was the door to his most significant legacy — the letters that became the blueprint for every Christian church in history.

Paul’s message to the Corinthians invites me to see my limitations as gifts from God to keep me humble and dependent on Christ. It reminds me that these impediments drive me to draw daily strength from Christ. These limitations are the windows that witness the power of Christ in a world filled with weakness. Paul invites me to see my impediments not as limitations to my life, but as a door to my most significant legacy.

We are limited beings invited to live flourishing lives under the care of our compassionate creator. We will do well to learn the secret of being content in every situation (Phil. 4:11-13). Then, our weakness will become our strength.